Elise is alone. The game in which she stars, Broken Pieces, is a lonesome experience. In it, Elise explores the abandoned french seaside town of Saint-Exil, armed only with a handgun, a magical puzzle-solving bracelet, and whatever materials she can find. However, she is no outsider. Elise lives here, somehow the only one left behind in this catastrophic event. The game is slated to release later in 2022, but I played around one hour of an early portion of the game and interviewed core designer Mael Vignaux, virtually, at GDC.

Broken Pieces, at least in the demo I played, is not especially scary. It is, however, magnificently eerie. It lacks the hazy ambiguity of something like Silent Hill, but rather relies on a haunting specificity. Saint-Exil is not an amalgamation of Americana or a wasted world, but rather an ordinary French village where things have gone very wrong rather recently. The streets are deserted and enemies do appear, but it feels like an ordinary morning could start at any time, that if Elise walked into a Café she might find people mulling about and be able to order a coffee and a pastry.

Render what you know

That sense of almost-life comes out of the developer’s experience inside French seaside villages. Vignaux lives in a town much like Saint-Exil. However, it’s not so much that the game takes place in the town where the developers live, more that they wanted to play in a similar place, with “the same kinds of buildings.” I’ve never lived in rural France, so my opinion on “accuracy” is moot. Nevertheless, the impression is one of simulacrum. Glittering cobblestone streets, blocky and small European cars, as well as plaque-laden historical sites grant Saint-Exil a particular character. The team’s modding experience, in my mind, prepped the team for this reconfiguration of assets. Instead of working with the re-contextualized pieces of a previous game, they work with the texture of a real world place. “We had the places before we had the game,” as Vignaux put it.

Vignaux then emphasized that the camera system came first, even before the places it would depict. In fact, the camera is key to the game’s eeriness; it builds out the distance between Elise and the player. Even in the demo, it’s quickly established that Elise knows more than the player does. She often refers to events outside of narrative view. She combs over memories of her past life with a familiarity the player cannot have. The player controls Elise while also feeling separate from her. The ability to switch between camera angles with the click of a button feels like scanning the feeds of security cameras. Earlier survival horrors games have played with surveillance, but this slight agency over sight makes the parallel even more explicit.

Specters of a hidden past

The camera system also reflects a general reworking of the genre’s trappings. The intent was to update the language of survival horror for a more contemporary mode, minimizing both cuts and player confusion. The problem is that survival horror doesn’t need updating. Resident Evil is not only a cold stone classic, but it holds up too. It can be confusing, but that confusion is by design more often than not. Slowly growing to understand its fractured mansion is a haunting thrill. In contrast, Broken Pieces is clear to a fault. In some moments, the game replaces RE’s lurid, striking images with clear but uninspiring compositions.

The combat suffers similarly. Elise fights shades, featureless outside of silhouetted gas masks and guns. Rather than relying on the ambiguity of sight, the game adds clear hit detection indicators. Elise also can dodge, making it easy to position her around threats. The combat falters in part because it’s far slicker than its inspirations. Both Silent Hill and Resident Evil gain a frantic pace because it is difficult to move and aim. Broken Pieces’ streamlining of these systems gives them clarity, but also makes them lose the intensity of their inspirations.

Ocean waves, the click of a cassette

Despite these struggles, Broken Pieces manages to feel worn in and haunting, thanks to the aforementioned attention to detail, even beyond the game’s visual simulacra. The team is small enough that everyone shares duties, but Vignaux crafted the majority of the game’s sound design, frequently utilizing the environment around him. He captures a lot of his own material because he “[doesn’t] want people to recognize the sound. Even if the sound is worse, it’s more unique.” This allows Vignaux to create specific moods and make each place in the game its own soundscape.

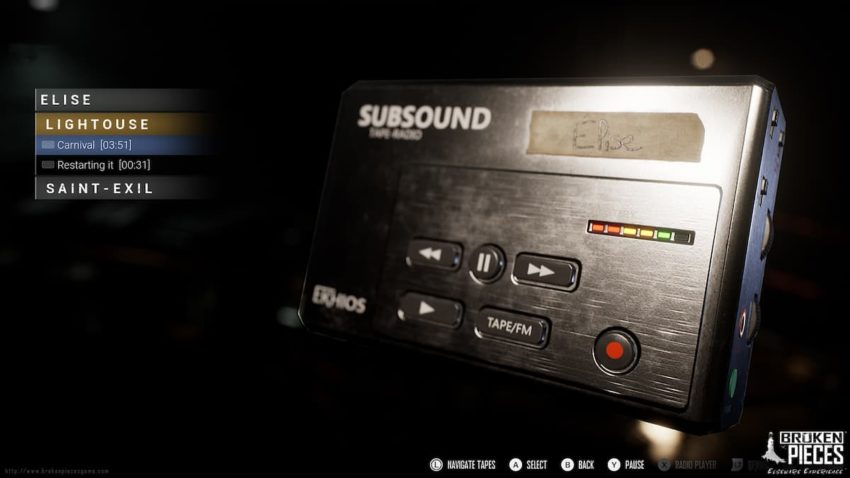

The emphasis on details shows up in the game’s verbs too. Like any good miniature post-apocalypse, you’ll find tapes scattered around, some from Elisé herself. When you open up the menu to listen to them, the game shows what’s written on the tape and presents a mock-up of a Walkman-like device. It hisses as the tape starts up and the device clicks in when you press the play button. The particular sound design gives Broken Pieces the material weight it needs to settle into eerie reality.

That reality feels yet eerier given the Broken Pieces’ emphasis on ecological disaster. When I asked Vignaux if climate change played a role in the game’s narrative; “I don’t want to spoil anything, but yes,” he said. That intention is obvious even in this early part of the game. One of the game’s sublimely surreal images is a massive pillar of water, jutting out of the ocean. At first, that pillar is only seen out of the corner of the frame. It’s a distant threat, a sign of what exactly is going on, but not lingered on. Additionally, there is already an emphasis on infrastructure. Elisé tasks herself with reactivating the hydropower at the local lighthouse. Setting aside the mass disappearance of Saint-Exil’s citizens, there is a sense that this town’s needs have been left behind and that the remnants of government oversight serve their own purposes. Though distant and abstracted, it’s hard not to feel global warming’s specter.

Toward the end of our meeting, when discussing overall development intention, Vignaux meekly declared, “I’m afraid to say the game is not fun.” The publisher rep was quick to step in clarifying how the game was fun, just in a different way than say, Mario. To me though, this is a great statement of confidence. Whether it succeeds or not, Broken Pieces is a game with serious concerns on its mind, with aesthetic ideas beyond the obvious and catchy. It falters only really when it chases the slickness of contemporary releases. It might not be “fun,” but in this limited form at least, it’s pretty damn compelling.

Published: Apr 8, 2022 01:06 pm