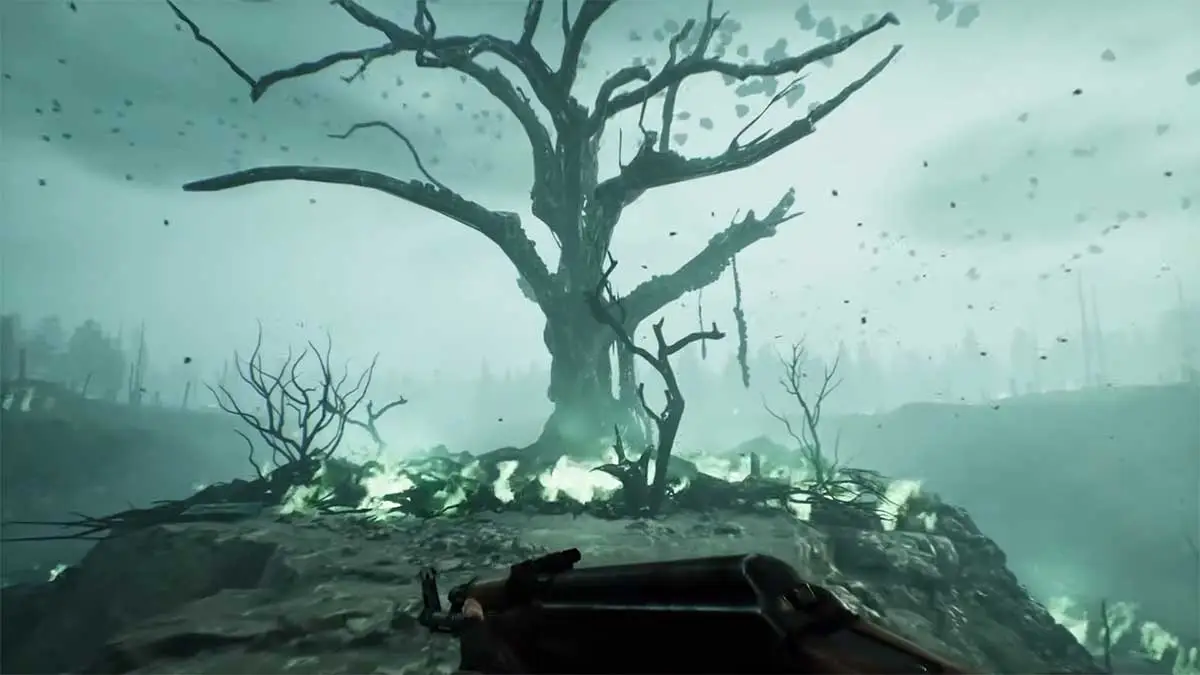

Chernobylite, the new “science-fiction survival horror experience” from The Farm 51 Games, is jank. It is a marvel of engineering that cannot possibly contain the vast energy within it, but one can still marvel at the attempt. Like the “sarcophagus” around the failed V.I. Lenin nuclear reactor at the center of the game’s setting, Chernobylite is a leaky, perhaps doomed mess, but the world is so much better for it.

As a game, this one is oftentimes downright not fun to play. That’s okay. Many of my favorite experiences with video games are with abrasive, difficult games, particularly buggy Russian ones like Pathologic and Stalker. Stalker is the obvious comparison: both games are first-person shooters set in the exclusion zone surrounding Chernobyl and Pripyat, and both follow an outsider navigating the world of “stalkers.” They directly reference Andrei Tarkovsky’s films and represent the bitter surreality of life in the half-life of a doomed system. Whether that system is capitalism or communism or fascism or a nuclear reaction is irrelevant: systems break down, and when they do, we confront the fallout.

Those confrontations with lives irradiated by disaster, addiction, turmoil, and loss are what make Chernobylite so good, to the point that I can make an unqualified recommendation to anyone who loves video games as a storytelling medium: get into this.

The survival, crafting, and gunplay mechanics are all serviceable, helpful for inducing the “flow” state that creates immersion and investment in interactive art, but they all very quickly become chores in a way that works here. While it is possible to plow through the zone, guns blazing as bodies pile up around you, to do so requires an investment of time and resources. Each firefight causes not only physical harm, but also psychological, which can only be addressed by guzzling alcohol. This image of our hero as a single-minded killer on an alcohol-induced rampage in the pursuit of a literal ghost is not a flattering one, and the people you meet are quick to tell you so.

Even the most calculating and vengeful mercenaries in the zone are rarely cruel, and they generally view mercy and cooperation as the path of least resistance. This is a space where war is a generalized fact of survival, and the practice of warfare is amoral: it is simply a science of survival, akin to hunting or electrical engineering. When a science such as warfare or power generation is practiced, there are emissions that are toxic to human life, and we, in turn, must deal with them, which manifests in Chernobylite as a highly involved (if not intricate) web of resources.

That’s Chernobylite’s loop: from a single desire, return to the zone and find the truth, there are many consequences. It’s a tragedy that plays out in all of the game’s systems, often at the cost of fun. Murder, like most of the pursuits one can take up in a video game, is often just another form of labor. Each firefight is mentally taxing, where the simple act of lining up a shot against these poorly animated targets can be exhausting, and for that reason, it is often better to avoid violence wherever possible. It is a cynical kind of non-violence, where one avoids killing simply because one grows tired of the process and consequences of it.

Along the way, you are party to a fascinating journey: that of an exiled scientist returning to the site of a long-forgotten trauma in order to reach some kind of understanding. The structure of investigations, missions, and heists is economical and compelling as a pacing device, and it also helps to highlight the dubious nature of our protagonist, Igor.

Igor is easy to despise. The player has a great deal of input about his precise actions, but his motives are obsessive, patronizing, and consistently focused on his late wife, Tatyana. If the Chernobyl nuclear disaster was a story about perestroika, human fallibility, the futility of scientific, or political revolution, or anything else, Igor almost certainly wouldn’t know that. To him, it was a story of personal loss for which he still needs to find someone to blame. This is a psychological need for which he will go to any length, even when it alienates his allies or enrages the very ghosts that he seeks out.

During the course of his investigation, Igor indulges his pettiest, most banal impulses. Presented with information about treason and coverups that could rewrite history, Igor remains squarely focused on questions of jealousy and marital fidelity. The fact that he will take this paranoid instinct to the point of staging an armed inquest into the zone is, if nothing else, interesting. Like the protagonists of Pathologic or Apocalypse Now, it is easier to accept Igor as a character when you also accept that you don’t have to like him to hear his story. Initially, I was incredibly off-put by the dead wife trope, but in the end, I’m grateful that I stuck it out long enough to accept that I’m allowed to hate Igor, as long as I understand his journey well enough to survive it from the driver’s seat.

That acceptance is everywhere in the zone of Chernobylite: each side character is animated by some contradiction of viciousness and grace that allows them to survive in the zone, carefully balancing the rationality of survival against the madness of survival inside of the zone. Very quickly, you will find yourself inside this same balancing act. Systems often fail, altruism is a survival skill, and trust is an asset.

In our particular time in the real world, where (late) Capitalist Realism is the phrase and, arguably, the system of the era, Chernobylite is a work of (late) Socialist Fantasy. The figure of Lenin in particular looms large over laser beams, magic crystals, and zombies: his name was on the power plant that failed, the city of Leningrad is important to the personal histories of our cast, and some of the game’s key story beats play out at the literal feet of Lenin’s statue. The question of the era is loyalty: how can one remain true to anything when reality itself is coming apart at the seams? Whether that breakdown is a political rift, a lovers’ spat, a nuclear disaster, an aching hunger, or a bullet wound, Chernobylite dedicates itself to stories about those breaking points, and the human drama that comes with them.

If you have the heart and stomach for janky immersive sims from Eastern Europe, play Chernobylite. I’ve been wrong before, but I think this could be a cult classic in the making, or at the very least, the studio behind it is one to watch.

Final score:

6 / 10

| + | Ambitious story with memorable characters and dialogue |

| + | Stunningly realized setting and cinematics |

| + | Eccentric and perfectly suited for a certain niche of players |

| – | Unfocused execution feels disjointed, clunky, and at times unfinished. |

| – | A first-person shooter where combat is by far the most abundant, and also the worst part of the game. |

Published: Jul 28, 2021 11:18 am