Do you ever wonder what happens in a Mario world after you leave? In Super Mario 64, the worlds behind the paintings are little ecologies, small worlds that you must learn the rules of in order to progress. 3D platformers broadly have an environmental intimacy, forcing players to learn the rules and interactions between a variety of creatures and landscapes. Generously, this relationship is fleeting. Harshly, it is extractive. Mario and Banjo are in their respective colorful worlds to get something and then leave. The place does not change them. They only change it.

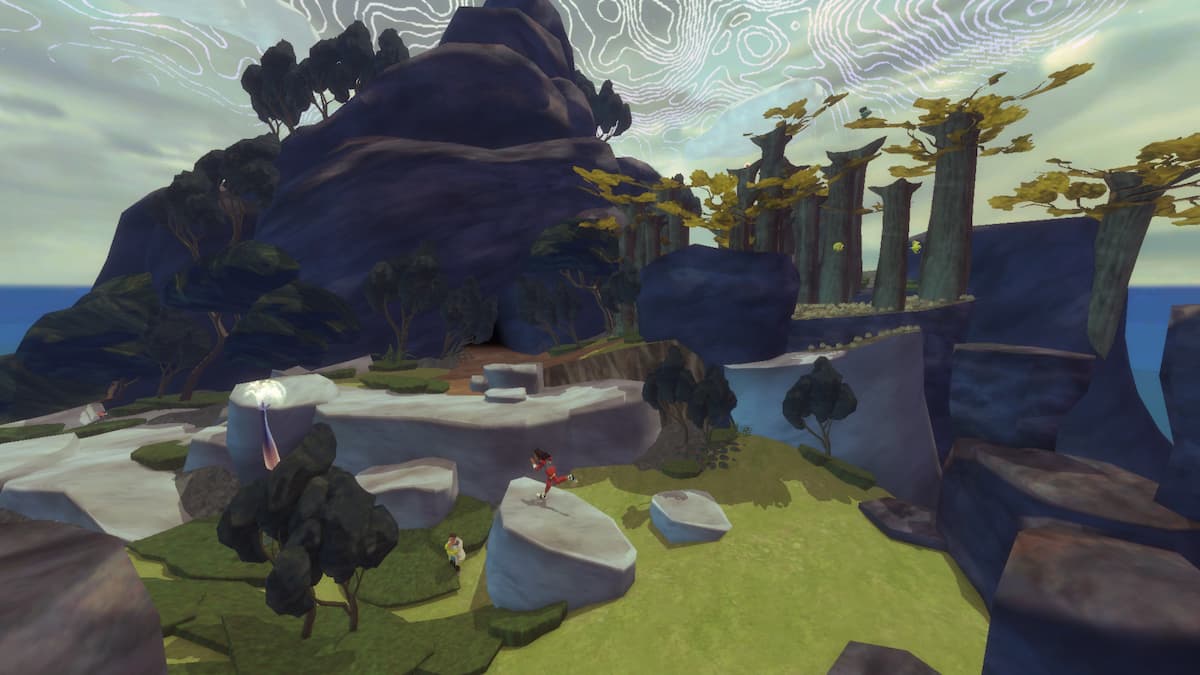

Instantly, Sephonie draws comparisons to other 3D platformers. The trio of protagonists explore the titular island’s caverns, forests, and dreamscapes. As they find and interact with ecology shifting key species, they learn more about themselves and the mystery at the heart of the island. All the while, the trio gains new abilities and leap their way through escalating, difficult challenges. However, like Analgesic Productions’ previous titles, Sephonie stakes its claim in quiet subversion, rather than nostalgic recreation. Unlike its influences, there is nothing to extract. Each member of the aforementioned trio is a biologist. They genuinely desire to learn more about the island, though the specter of their international research team hangs over every discovery. There are optional collectibles, but they are trinkets and memories that our scientists brought to the island, not the island’s own resources. Forgotten photos, beloved recipes, even just the recollection of climbing in middle school fill out the collectible parts. Even the biologists’ new abilities come from a deeper understanding of Sephonie, rather than some powerful trinket.

Wallrunning as a scientific method

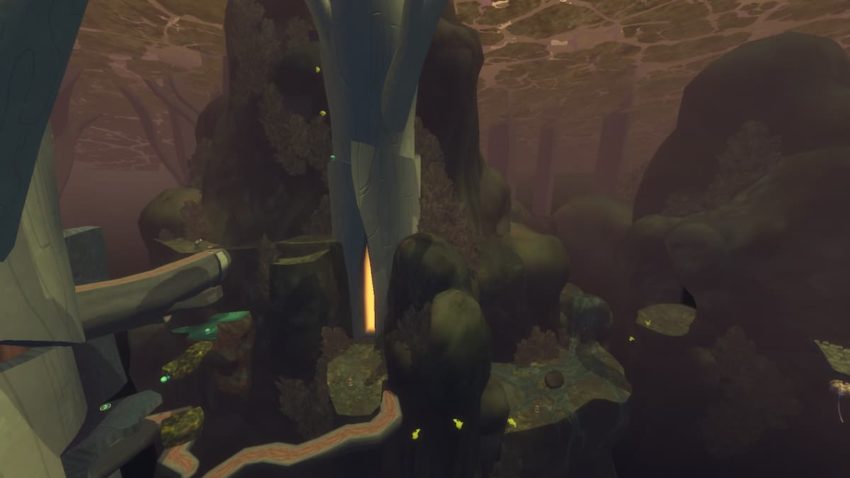

More than most video game worlds, Sephonie is a little place. Though static in code, it shifts and changes in contact with the protagonists. Every creature you encounter has a logical place in the ecosystem, making exploration of the island a network of interconnected relationships. That interconnectedness extends to the stone and wood the scientists will run on, the curve of a cliff wall, the uneasy safety of a mushroom cap. In order to discover the island’s creatures after all, the scientists must move through their environment. Like most platformers, the game builds out a language of items and abilities. Its primary innovation is tying that language to a well-drawn world. It helps that connecting with the island’s life is a game of its own — a puzzle game to be exact.

OYNX, the science fiction device which grants the scientists their physical power, also collects data. It can scan flora and fauna to help uncover their individual place in the ecosystem. Scanning involves placing multicolored Tetris-like tiles on a grid and attempting to chain large groups of the same color together. Each creature scanned grants another tile for the player to use. Each new tile helps enable a further understanding of new creatures. It is not just uncovering a clever new mechanic, but growing into a more intimate connection with a fictional, material world.

Key too to that connection is the sense of physical embodiment. Sephonie doesn’t feel snappy, it feels weighty. Sprinting creates momentum, making it difficult to slow down or stop readily. Wall running doesn’t work if you are too parallel, forcing a more exact consideration of positioning. The game’s most extravagant ability is a dash, letting you get a quick jump if you are close enough to a wall. These lean tools are at once strange and familiar. They are the direct consequence of a game that doesn’t take conventional wisdom as law. Again, they require that you lean on an understanding of the environment around you, rather than using your own abilities to transcend it.

Abstract realism

Because of its unconventional approach, Sephonie might throw off the experienced platforming fan. For example, you can move the camera 360 degrees around your chosen character, but the game doesn’t direct your vision the way something like a Mario game does. This means that the proper path can be tricky to find or might be obscured by an errant model. That would be easy to write off as an inconvenience, a limitation of Sephonie’s budget. In reality though, it’s a key element of what makes the game so beguiling and strange. Sephonie wants you to break it. It requires you to consider the ends of its possibilities, the places where its hard platforms fade into endless voids and unreal color. To do that, it requires that you pay attention.

In this abstraction, Sephonie reaches a reality that most games of its ilk cannot muster. By approximating a weighty body that moves through an interconnected ecology, the game leans on suggestion rather than realism. An attempt to create a “real” seeming island would only feel fake, even in the false splendor of expense. Instead, it creates something real in a way a sci-fi novel is real. The island is a construct, a metaphor dense with contradiction and nuance, something more truthful than the truth.

So when Sephonie becomes just as psychological as ecological, when deeper caverns reveal approximations of the midwest’s endless fields or Tokyo’s skyscrapers, it feels natural. You see, the relationship between scientists and subjects is fluid. Sephonie studies the scientists as much as they study it. Their pasts and presents become an integral part of the island’s history and future. The island might seem isolated and alone, but their presence connects it to a recognizable, broader world.

The personal is ecological

This is part of the game’s overall arc; the obvious layer of science fiction folds in and out of personal, contemporary narratives. Though Sephonie is entirely fictional, the scientists all come from “the real world.” Amy Lim is Taiwanese-American and hails from Bloomington in the U.S. Riyou Hayashi is Japanese-Taiwanese and lives in Tokyo. Ing-wen Lin lives in Taipei. In contrast to the approximate caricatures of many 3D platformers, Sephonie concerns itself with real nations. It would be easy to make this trio into simple symbols, representatives of specific cultures or ideals. However, this kind of hamfisted metaphor never enters into Sephonie’s sphere. Instead, it explores massive, world-shaking ideas through three distinct individuals and the unusual island they briefly call home.

The three characters do share some cultural background and similarities. The player can play as any of the three scientists at any time and their abilities are all exactly the same. This makes a quiet argument that all three are equally able to do this work. They all speak English. All have similar professions, qualifications, and expertise. All work for biology labs, with ties to their nation’s governments, which are now collaborating with each other. However, their experiences are all individual, as differentiated by their nations as by their personalities. As the island changes, each scientist gets extensive text and cutscenes dedicated to fleshing out their bodies and souls. This is where the game gets its most poignant and gorgeous narrative work. Using prose, poetry, 3D models, and dioramas, as well as faded digital collage, Sephonie builds out a multidimensional portrait of what brought Amy, Riyou, and Ing-Wen to this island. Beyond any other similarity or difference, they share this place and rely on each other to survive.

The ecological is political

Their relationship is where Sephonie gets its drama and its beauty. The events that lead these three to be together are at once arbitrary and destined. Amy grew up in a family of biologists, three generations all working at the same lab in Bloomington. Her competence can render her closed off. Riyou is a relentless worker, focused and determined, mostly to avoid his own feelings. Ing-Wen is sensitive and caring, but often feels disconnected from the wider world. Her girlfriend, Light, lives far away, and so Ing-Wen most readily feels the cruelty of borders. These little dramas unfold deep within Sephonie’s caverns, in the aforementioned dreamscapes and collages. Sephonie’s first contact with humanity, with these specific people, morphs it into a microcosm of their lives. Sephonie is just a little island, but it is also the whole world.

With that global perspective comes terror as well as joy. In one grim moment, the trio considers what the governments back home will do with the information they’ve discovered and what they themselves could do to hide the most exploitable parts of it. Shinji wonders if the U.S. could, or would, make a bioweapon. Amy only nods along, as aware of the possible consequences of their journey as he. Empire hangs over their lives. In her dreamscape, Amy recognizes that much of her center’s research is funded by U.S. government contracts. Back in Japan, Riyou’s co-worker makes a racist joke upon discovering that he can speak Chinese. The same connection that enables the trio to meet each other is bound up in the past and present violence of empire.

The political is personal

Fundamentally though, Sephonie is optimistic. Even as it stares into the heart of the world empire has made, it fosters a vivid, ecological picture. Exploring Sephonie unveils a natural world that is not dead or even dying, that is not separate from humanity, not able to be contained or tamed or repaired. Rather it dwells in every part of our being, in the cybernetic enhancements we use to live, in microchips and houseplants, telephone wires and front lawns. The question is whether we can believe in that connection, choose to embrace it, or whether we wish to mine our very flesh for profit.

To put it briefly, Sephonie is a miracle. It swings between life and death, classic genre convention and thoughtful subversion, the mind-bendingly global and the heartbreakingly personal. It holds its own against giants of science fiction by refusing to be pinned down, floating between genre and tone with the unknowable elegance of flight. It’s tragic and triumphant, a vision of the narrative work games could do without the frivolous constraints that tie them to convention. Like the island itself, Sephonie layers metaphors to build a distant vision of a tragic and hopeful future.

Final Score:

10 / 10

| + | Unique platforming and puzzle-solving encourage an ecological perspective |

| + | Gorgeous and multilayered visuals reflect a global, interpersonal narrative |

| + | Well-defined, human characters flesh out an ambitious, genre-bending story |

| – | The game’s unconventional approach to classic ideas might take some adjustment |

Gamepur team received a PC code for the purpose of this review.

Published: Apr 12, 2022 04:52 pm